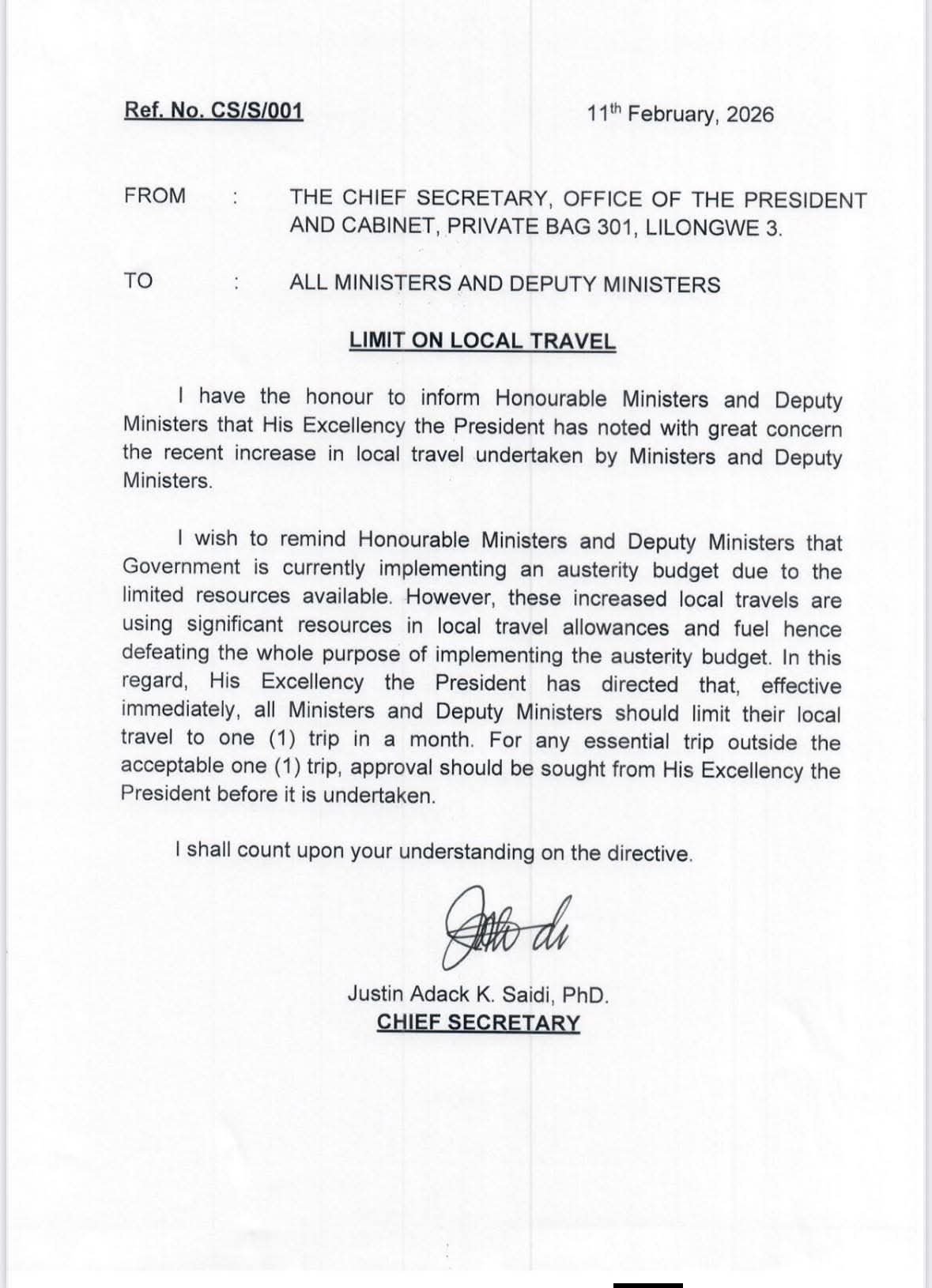

President Professor Peter Mutharika’s decision to restrict Cabinet Ministers and their deputies to just one local trip per month has struck a chord with many Malawians, who see it as long overdue discipline in a government culture that has become too comfortable with constant movement and allowances. The directive, communicated through Chief Secretary to the Office of the President and Cabinet, Justin Saidi, comes against the backdrop of a strained national budget. Saidi says the President acted after noting a sharp increase in local travel by ministers, at a time when government is officially operating under an austerity budget.

In simple terms, the message from State House is this: Malawi cannot afford a travelling government. Saidi’s statement is blunt. He reminds ministers that the country is facing limited resources, yet travel allowances and fuel costs are rising.

This, he notes, directly contradicts the spirit of austerity. “However, these increased local travels are using significant resources in local travel allowances and fuel hence defeating the whole purpose of implementing the austerity budget,” the statement reads. What makes the directive even more significant is that any additional trip beyond the one allowed per month now requires direct approval from the President himself.

Read Full Article on Nyasa Times

[paywall]

This centralises control and sends a clear signal that travel is no longer a routine entitlement, but an exception that must be justified. From an analytical perspective, this move exposes a deeper problem in Malawi’s governance culture. For years, public office has been associated with movement—convoys, workshops, launches, and “official visits”—often with minimal outcomes but guaranteed allowances.

The office, where policies are meant to be designed, monitored, and evaluated, has gradually become secondary. The President’s instruction challenges this norm. It redefines a minister’s primary duty as staying put, managing their portfolio, supervising departments, and delivering results from the desk, not from the road.

For a country grappling with debt, rising costs of living, and shrinking fiscal space, the symbolism is powerful. Fuel is expensive. Allowances consume millions.

Yet most Malawians struggle to afford basic transport, let alone justify government-funded trips that rarely translate into improved services. This is why public reaction has been largely positive. Many citizens see the directive as rare political honesty—an acknowledgment that government itself must tighten its belt before asking ordinary people to endure hardship.

Still, the real test lies in enforcement. Malawi has a long history of good directives that quietly die in practice. If ministers continue travelling under vague labels like “urgent business” or “strategic engagement,” the policy will become another empty announcement.

But if implemented strictly, the directive could mark a shift in how public resources are managed. It could reduce waste, improve office productivity, and restore some credibility to the idea of austerity. At its core, Mutharika’s message is simple but uncomfortable for those in power: you were not appointed to tour the country—you were appointed to run it.

[/paywall]

All Zim News – Bringing you the latest news and updates.